RELATED UPDATE: Texas District Court Preliminarily Enjoins FTC’s Non-Compete Rule Only for Named Plaintiffs (July 9, 2024)

The Federal Trade Commission’s April 23 final rule banning most non-competes for workers in the United States, including clinical and non-clinical employees in the healthcare industry, undoubtedly will raise questions from healthcare industry leaders.

That’s why McGuireWoods has compiled the following essential list of FAQs and detailed answers, which supplements the firm’s recent legal alert on the final rule’s key takeaways and general applicability to specific types of employers and employees.

The responses to these 15 questions largely provide the FTC’s gestalt in adopting the final rule and explain how the FTC may expect specific regulatory text to apply to the healthcare industry. By contrast, with a few limited exceptions, the responses generally do not include counterarguments against the FTC’s views, even where multiple court challenges address these topics. Ongoing litigation could shape the final rule’s scope and applicability or determine if the final rule becomes effective.

1. What does the FTC consider a non-compete under the final rule?

a. The FTC defines a non-compete clause as a “term or condition of employment that prohibits a worker from, penalizes a worker for, or functions to prevent a worker from (i) seeking or accepting work in the United States with a different person where such work would begin after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition; or (ii) operating a business in the United States after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition.” Such clauses can be contained in employment agreements, company policies, employee handbooks or an oral agreement.

Other agreements and restrictions, like non-disclosure agreements or agreements preventing former employees from soliciting customers, are not categorically barred by the FTC’s final rule. However, these restrictions could fall within the final rule’s prohibition depending on the particular circumstances and breadth of the restriction — for instance, if the agreement or restriction functions to prevent workers from obtaining employment or starting their own businesses. This is discussed further in response to question 14 below. Note, the FTC’s use of the term “employment” is not limited to W-2 status; the term employment means “work for [another] person,” and the FTC makes clear its view that a “worker” can include independent contractors, volunteers, owners and others providing a service under the terms of the final rule.

2. What businesses are covered by the final rule?

a. The final rule broadly applies to any worker who provides or provided a service to a person, with “person” defined as “any natural person, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity within the [FTC’s] jurisdiction, including any person acting under color or authority of State law.” Accordingly, the final rule broadly applies to most business types and sectors, with limited exceptions based on limits to the FTC’s rulemaking authority, including a potential exception for certain non-profit healthcare providers discussed in question 4 below. Under the final rule, for-profit healthcare facilities and entities, physician practices, private equity funds, other investment funds and lenders are likely restricted on use of non-competes.

3. Healthcare has unique features identified in comments to the FTC. Why didn’t the FTC design different rules for the healthcare industry?

a. In the final rule, the FTC described how it considered, but ultimately rejected, industry-specific rules with respect to non-compete restrictions, including a standalone section discussing healthcare-specific challenges to the proposed rule. While many industry participants provided comments to the FTC about the need for non-competes in healthcare (e.g., to maintain a level playing field with non-profit providers described below, and to protect clinical integration), the FTC noted that thousands of healthcare providers (the majority of those commenting from the industry) supported the proposed rule’s ban on non-compete clauses. Nearly every section of the final rule containing examples from the FTC’s rulemaking record includes public comments from healthcare providers supporting the final rule — describing lost access, patient choice and reduced wages stemming from non-compete clauses. Further, the FTC’s cited evidence for adopting the final rule included only one industry where the FTC asserted that the final rule is anticipated to reduce prices — the healthcare industry. Based on these actions and comments, it is unlikely healthcare industry-specific bifurcation of the final rule will be forthcoming from the FTC.

4. Does the final rule apply to non-profit and tax-exempt hospitals and other healthcare entities?

a. Potentially, but many non-profit and tax-exempt hospitals and other healthcare entities may fall outside of the FTC’s authority utilized in promulgating the final rule. Therefore, these entities would be permitted to maintain non-competition provisions restricting workers. In the event non-profit or tax-exempt entities are determined to fall outside the final rule’s ambit, it will be due to the FTC’s lack of authority to restrict the applicable entity’s activities and not a categorical protection provided by the FTC to non-profit or tax-exempt providers in the final rule. The FTC’s purported authority to promulgate the final rule is rooted in statutory language preventing persons, partnerships or corporations from engaging in unfair methods of competition. Under FTC authorizing statutes, a corporation is defined as an entity “organized to carry on business for its own profit or that of its members.” In the event the FTC does not have authority to restrict the activities of an applicable entity (e.g., a non-profit or tax-exempt healthcare entity not engaged in business for its own profit or that of its members), the final rule will not apply.

In the FTC’s discussion of the final rule’s applicability, the FTC noted that a non-profit or tax-exempt entity could fit within the definition of a corporation (noted above) if it is a profit-making enterprise. In other words, the FTC’s stated position is that a non-profit designation or tax-exempt status (including in the healthcare sectors) is not dispositive of the FTC’s authority over the entity or its analysis of whether the entity is profit-making, and therefore subject to the final rule. The FTC gave examples from the healthcare industry of tax-exempt healthcare entities — including physician-hospital organizations and independent physician associations — over which the FTC previously exercised jurisdiction in enforcement actions.

Many non-profit and tax-exempt healthcare providers, including hospitals, will likely lean on their designations to continue to utilize non-compete restrictions, but the FTC posits that “claiming tax-exempt status in tax filings is not dispositive” (emphasis added). The FTC states in a footnote that it “cannot predict precisely how many entities claiming nonprofit tax-exempt status may be subject to the Final Rule,” but noted that “some portion of the 58% of hospitals that claim tax-exempt status as nonprofits and the 19% of hospitals that are identified as State or local government hospitals in the data cited by [the American Hospital Association (AHA)] likely fall under the [FTC’s] jurisdiction and the Final Rule’s purview.” Non-profit and tax-exempt entities will likely challenge this position. Indeed, included in a statement shared with the media this week, Chad Golder, AHA’s general counsel and secretary, noted, “Three unelected officials should not be permitted to regulate the entire United States economy and stretch their authority far beyond what Congress granted it — including by claiming the power to regulate certain tax-exempt, non-profit organizations.”

5. Which workers and other individuals are covered by the final rule (e.g., does it apply to non-owner physicians, physician owners and partners, other clinical providers such as physician assistants or registered nurses, or independent contractors)?

a. The final rule broadly applies to “workers,” defined as “a natural person who works or who previously worked, whether paid or unpaid, without regard to the worker’s title or the worker’s status under any other State or Federal laws, including, but not limited to, whether the worker is an employee, independent contractor, extern, intern, volunteer, apprentice, or a sole proprietor who provides a service to a person.” As a result, non-owner physicians, physician owners and partners (as further discussed in response to question 12 below), all clinical providers, including physician assistants and registered nurses, non-clinical personnel, and independent contractors likely fall under this definition, if they are providing services to a person, unless an exception to the final rule applies. The applicable exceptions are discussed below. It will also be important to distinguish when a worker is “providing services” to a person, which appears to be the FTC’s touchstone for being a worker, even if such determination is not easily defined.

a. The final rule contains a limited exception for certain senior executives to retain non-competes existing prior to the final rule’s effective date, but companies and individuals are prohibited from entering into new non-competes with senior executives after the effective date. The final rule’s effective date will be 120 days from publication in the Federal Register, which has not yet occurred.

The FTC’s final rule describes a two-part test to determine whether an individual qualifies as a senior executive and when an employer can maintain the existing non-compete provision:

- the individual received at least $151,164 in total annual compensation in the preceding year; and

- the individual is in a policy-making position.

The final rule gives examples of senior executives, such as the business entity’s president, chief executive officer or the equivalent or any other officer of a business entity or natural person who has policy-making authority. This policy-making authority needs to be over significant aspects of a business entity or common enterprise — i.e., it cannot be over human resources or marketing alone, nor can it be limited to advising or exerting influence over such policy decisions. The FTC estimated 0.7% of workers will fall into this senior executive category and thus be eligible to continue existing non-competes.

The final rule also contains a bona fide sale of a business exception, discussed in question 11 below.

7. Can outside activities be restricted during employment (e.g., moonlighting)?

a. Yes. The FTC defines a non-compete as a term or condition of employment that prohibits, penalizes or functions to prohibit a worker from (a) seeking or accepting work with a different person after the conclusion of the current employment or (b) starting a business after the conclusion of the current employment. Therefore, concurrent exclusivity provisions, outside activity restrictions, or other non-competition restrictions during the term of a worker’s employment, such as prohibitions on moonlighting for other healthcare organizations while a current employee, would not fall under what FTC considers a non-compete.

The FTC also specifically contemplates that some employers may utilize alternative restrictive covenants for protectable interests in lieu of non-complete clauses, such as non-disclosure agreements, training repayment agreement provisions, and other agreements that do not prohibit, penalize or function to prohibit employment from the items listed in the prior paragraph. Like other elements of the final rule, such arrangements may still be subject to other legal and antitrust scrutiny depending on the exact circumstances of the arrangement. These provisions and some of the FTC’s stated limitations in response are discussed further in question 1 above and 14 below.

8. What actions do healthcare providers need to take with respect to any existing non-competes for workers?

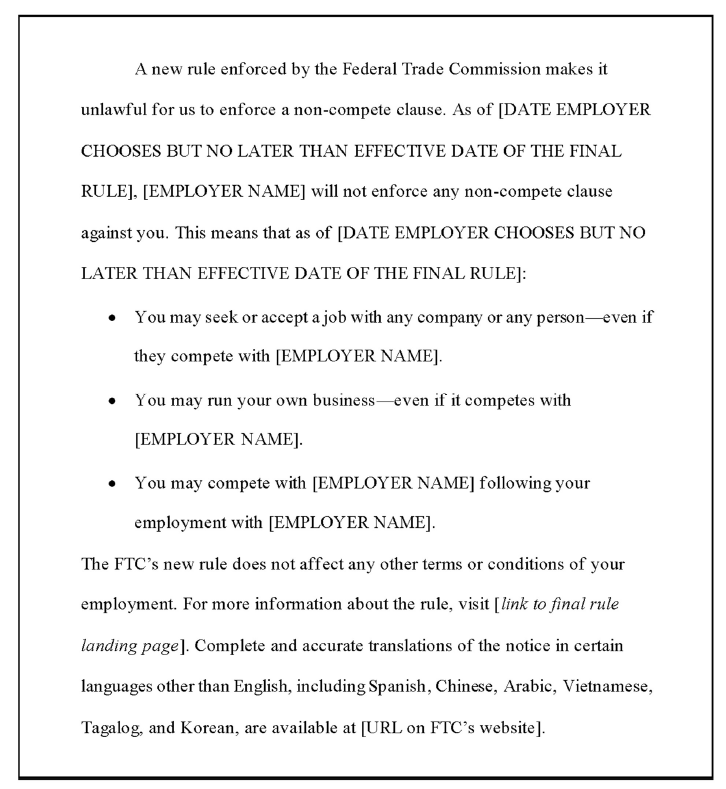

a. The final rule requires employers to provide a clear and conspicuous notice to workers (including those no longer working for the entity as described in response to question 10 below) subject to an existing non-compete by the final rule’s effective date (i.e., 120 days from the final rule’s publication in the Federal Register, which has not yet occurred). The notice must say “that the worker’s non-compete clause will not be, and cannot legally be, enforced against the worker.” The FTC provides the following sample notice in the final rule.

Current and potential legal challenges to the final rule, some of which are described in McGuireWoods’ April 24, 2024, legal alert on the final rule, may delay or alter this notice requirement. Furthermore, no notice is required if the employer has no record of a street address, email address or mobile telephone number for the relevant worker. Finally, the FTC stated that an employer can fulfill its burden by providing this notice to all workers, even those without a non-compete clause.

9. What if I’m in a state such as Texas, where state law mandates physician employment non-competes have buyout clauses? Are those non-compete provisions now prohibited or does state law pre-empt?

a. No, state laws governing non-competes do not exempt an employer from compliance with the FTC’s final rule. The FTC’s position is that the final rule supersedes state laws that “permit or authorize a person to engage in conduct that is an unfair method of competition.” The FTC’s position is that the final rule would prohibit new non-competes and end existing non-competes for non-senior executives in states like Texas that specifically allow physician non-competes, even if such provisions met certain required conditions. Similarly, the FTC intends the final rule to restrict use of non-competes in states like Illinois that require certain notice periods and specific consideration before entering non-compete provisions.

On the other hand, the final rule preserves state authority with respect to restrictive covenant laws, if they do not authorize non-competes in contradiction with the final rule. For instance, Texas’ buyout clause requirement is likely to still be valid if an employer sought to enforce an existing non-compete clause against a physician who also qualified as a senior executive. Similarly, state law requirements that non-competes must be reasonably tailored to a protectable interest will still apply in the context of the sale of a business carve-out described in question 11 below.

a. Yes. The final rule defines a worker as “a natural person who works or who previously worked…” (emphasis added). Therefore, the final rule applies to employees already bound by an active non-compete. The FTC also notes that “former workers” subject to a non-compete must receive the above-described notice that the non-compete is no longer enforceable, unless an exception applies, or the employer has no record of a street address, email address or mobile telephone number for the former worker. The final rule’s prohibition does not apply where litigation related to a non-compete clause already has begun.

a. No. The final rule includes an exception that permits non-competes “entered into by a person pursuant to a bona fide sale of a business entity, of the person’s ownership interest in a business entity, or of all or substantially all of a business entity’s operating assets.” There appears to be significant ambiguity as to what the FTC considers a bona fide sale of a business, ownership interest or operating asset (i.e., the final rule does not define these terms). The FTC “decline[d] to specifically delineate each kind of sales transaction which is not a bona fide sale under the exception.” That said, the FTC stated it “considers a bona fide sale to be one that is made between two independent parties at arm’s length, and in which the seller has a reasonable opportunity to negotiate the terms of the sale.”

By contrast, the FTC does not consider the use of springing non-competes (in which a worker agrees at hire to a non-compete in the event of a future sale) or forced redemptions (where a worker may be required to sell shares in an entity if a certain event occurs) as a bona fide sale of a business entity. There likely will be limits to what is deemed a bona fide sale transaction with respect to the final rule. Litigation regarding the final rule will refine the sale of a business exception.

a. This analysis may depend on the factual scenario of the arrangement. The FTC’s final rule states that the definition of worker does not need to include “an owner who provides services to or for the benefit of their business because the definition already encompasses the same” (emphasis added). Therefore, the FTC’s position for physician services businesses is expected to be that a physician practice governing document’s non-compete provisions are subject to the final rule’s ban to the extent they restrict workers in the enterprise, although the FTC notes that in limited instances physician partners may be senior executives that would allow existing non-competes to remain in place as described in question 6 above. Although physician services businesses will likely face the restrictions above, there could be restrictive covenants associated with an individual’s investment in healthcare ancillary or non-professional businesses that do not fall within the final rule’s prohibition. For example, the clause may not be a “term or condition of employment,” since the investor may not provide professional or other services for such business as a worker, and instead is only an investor in the applicable business. Examples of these businesses in the healthcare industry could include surgery centers, medical real estate entities, equipment leasing companies and management companies. Under one reading of the FTC’s final rule, a non-compete clause may be enforceable against investors as they may not be considered employed or deemed workers under the meaning of the final rule. Therefore, it is possible these businesses will be permitted to retain non-competes that restrict investors, which is an area McGuireWoods will continue to review and monitor.

13. Does the final rule restrict business-to-business non-competes?

a. No. The final rule does not ban business-to-business non-competes, but business-to-business non-competes that attempt to prohibit individual workers from competing with a former employer will likely be prohibited by the final rule. Given the FTC’s broad stance against all “worker” non-compete clauses, it will be critical to consult counsel to make sure that business-to-business non-competes are reasonable and appropriate in scope. For example, the final rule does not prohibit a non-compete between two medical practice entities, but it appears to prohibit a non-compete that prohibits a former employee of one medical practice from working for another medical practice or starting their own enterprise through the business-to-business agreement. Business-to-business non-competes could still be unenforceable or illegal under other federal or state antitrust and competition laws.

14. What does the final rule mean for non-solicitation, confidentiality and trade secret clauses?

a. The final rule does not render non-solicitation, confidentiality, or trade secret covenants unenforceable. However, the FTC noted that non-solicitation covenants “can satisfy the definition of non-compete … where they function to prevent a worker from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business after their employment ends.” The FTC’s position on non-solicitation covenants applies to covenants pertaining to non-recruitment, confidentiality, trade secrets, and non-disclosure as well. To the extent any such covenant “functions to prevent” workers from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business after their employment ends, the same would be treated as a functional non-compete.

That said, as discussed in response to question 1 above, because non-solicitation, confidentiality, non-disclosure, trade secret and non-recruitment covenants are not per se unenforceable, they could be reasonable alternative covenants for healthcare companies to protect their legitimate business interests if efforts to implement new or revise existing covenant terms are narrowly tailored and do not prohibit employees from working for other entities after the term ends. Failure to narrowly tailor such covenants increases the risk that the same will be treated as a functional non-compete unenforceable under the final rule, which could lead to a sanction or civil penalty.

15. What are my next steps?

a. Take a deep breath. The final rule will take effect no less than 120 days after the date of publication in the Federal Register (which has not yet occurred), and the rule likely will face legal challenges that could delay the effective date, so healthcare companies have time.

Many healthcare providers may want to begin planning to bring business practices into compliance with the final rule or reviewing to understand the impact to their businesses. To that end, healthcare companies may want to assess the impact on their businesses, reviewing those within their employ who have non-compete provisions; assess other restrictive covenants to see if the respective agreement’s confidentiality and solicit provisions accomplish what is necessary without overstepping with respect to the FTC’s concern; and begin to develop a strategic plan, including whether to enter new restrictive covenants before the final rule’s effective date. McGuireWoods can work with healthcare providers considering each of these proactive steps as there is not a one-size-fits-all approach — each presents its own risks and benefits. Healthcare providers should continue to monitor updates as the court challenges may impact initial organizational decisions in response to the final rule.

McGuireWoods will continue to publish guidance related to the final rule and litigation challenges. For questions related to the final rule and its application to the healthcare industry, please contact one of the authors of this article.